Authorities report that a recently enacted law in Mississippi aimed at reducing the incarceration of individuals solely due to their mental health treatment needs has resulted in a decline in the number of individuals with severe mental illnesses held in jails. However, the accompanying data presents inconsistencies and remains incomplete.

A state agency, various counties, and community mental health centers – each playing a part in implementing the new legislation – provided significantly different figures regarding the number of individuals who were incarcerated during the civil commitment process in the initial three months following the law's enactment.

Community mental health centers have indicated that 43 individuals were incarcerated between July and September 2024, which is significantly lower than the 102 individuals reported by the Department of Mental Health. Furthermore, the department's count is probably an understatement, as it only accounts for those who were subsequently admitted to a state hospital. This means that the total does not encompass individuals who were jailed prior to their release or those who sought treatment in other facilities.

Adam Moore, a spokesperson for the Department of Mental Health, shared with Mississippi Today that he was unable to clarify the inconsistency.

Counties’ reporting of commitment data has been patchy since lawmakers mandated chancery courts to report psychiatric commitment data to the state in 2023. Only 43 of Mississippi’s 82 chancery court clerks complied and submitted the most recent report. Those counties reported a total of 25 people being held in jail during the same period while in the civil commitment process.

Six counties—Alcorn, Choctaw, Holmes, Issaquena, Kemper, and Sharkey—have yet to submit their data to the state. The only response received by Mississippi Today came from Choctaw County Chancery Clerk Steve Montgomery, who claimed he was unaware that the court had failed to report the information.

“It has been quite variable. In certain areas of the state, it has been completely lacking,” stated Rep. Sam Creekmore IV, a Republican from New Albany and the chair of the Public Health and Human Services Committee. “This inconsistency makes it extremely challenging for us to assess our performance, whether it’s good or bad, since the data isn’t reliable.”

Creekmore sponsored changes to Mississippi’s civil commitment law in 2024 and reporting requirements in 2023. He said he plans to propose legislation this year that would ensure more counties submit mandatory data.

"He expressed that the incompleteness of our data makes it extremely difficult to enact modifications to the new civil commitment laws."

After changes to the civil commitment law passed last year, Creekmore said the Department of Mental Health would “police” counties to ensure compliance. But the agency told Mississippi Today and ProPublica it would educate county officials and mental health workers on the new law, but wouldn’t enforce it.

According to Moore, the spokesperson for the agency, the Department of Mental Health issues quarterly reminders to clerks regarding reporting deadlines, offers training videos and written guidelines, and has set up a help desk to assist with any technical inquiries.

The state Legislature approved changes to the state’s civil commitment law in May after Mississippi Today and ProPublica reporting revealed that hundreds of people with no criminal charges were held in Mississippi jails each year as they awaited involuntary mental health evaluation and treatment. They frequently received no mental health care in jail and were treated like criminal defendants.

The new law went into effect in July 2024. Now, local community mental health center staffers screen people who are reported to be a potential danger to themself or others before they are taken into state custody and must note why a less restrictive treatment is not an option. A person cannot be held in jail unless all other options for care have been exhausted, they are “actively violent” and never for more than 48 hours.

The recent legislation mandates that individuals in crisis consult with mental health professionals as a priority. These assessors have the authority to propose involuntary commitment or recommend more appropriate voluntary treatment alternatives, thereby bypassing the civil commitment procedure altogether.

According to reports from community mental health centers, more than 500 individuals were redirected to a treatment option that is less restrictive than civil commitment. Additionally, during the initial three months following the implementation of the new law, mental health professionals carried out 1,330 screenings for commitment across the state.

According to Moore, the wait times in jails for individuals who have been mandated by a judge to be admitted to a state hospital have reduced by a day and a half over the past year. However, the agency lacks information on the duration individuals spend in jail prior to receiving a commitment order from a judge.

"Butch Scipper, who has held the position of chancery clerk in Quitman County since 1992, remarked, 'In my time in office, I believe this is the most significant change they have implemented with the new law.'"

He, similar to numerous other chancery court judges, sheriffs, and mental health experts, has praised the initiative for helping Mississippi reduce its historical reliance on jails for accommodating individuals with serious mental health issues who are awaiting treatment at the state hospital.

Most states do not regularly hold people in jail without charges during the psychiatric civil commitment process. At least 12 states and the District of Columbia prohibit the practice entirely. And only one Mississippi jail was certified by the state to house people awaiting court-ordered psychiatric treatment in 2023.

Sheriffs, who have historically criticized the challenges of accommodating individuals with mental health issues in jails as unsuitable and hazardous, have generally expressed their backing for legal reforms.

“It’s great news for the sheriffs, as they prefer not to have sick individuals in their jails,” remarked Will Allen, the legal representative for the Mississippi Sheriffs Association. “They definitely do not want to see individuals who haven’t committed any offenses behind bars.”

Obstacles to execution

Enforcing the law has been difficult for regions of the state that lack adequate resources, especially in locations that do not have access to nearby crisis stabilization units, which offer temporary care for individuals experiencing psychiatric emergencies.

Even in regions with ample resources, the scarcity of crisis beds may compel counties to either transfer patients or accommodate them in a nearby private treatment center, often at the counties' own cost.

Between July and September 2024, community mental health centers operating the state's crisis stabilization units documented this occurrence 114 times, attributed to constraints in bed availability or staffing levels.

The state now has 14 crisis stabilization units funded by the government, offering a total of 204 beds, an increase from the previous 180 beds last year.

According to Chancery Clerk Kathy Poyner, the limitations on housing individuals in jail have turned into a "nightmare" for Calhoun County, located over 30 miles from the closest crisis stabilization unit.

"We don't have any other options for them," she stated. "We can't bear the cost of a psychiatric unit. Rural counties simply lack the financial resources."

Law enforcement personnel have a legal obligation to transport patients. However, certain counties contend that this responsibility can be both expensive and time-consuming for their officers.

According to Adam Moore, a spokesperson for the Department of Mental Health, the crisis stabilization unit beds in the state were never completely occupied throughout fiscal year 2024. He noted, “There is consistently at least one CSU bed available somewhere in the state, provided that a sheriff is ready to transport an individual.”

Creekmore said he also hopes to introduce a bill for a pilot transportation program that would offset the costs of transporting patients to mental health treatment. The program would be modeled after a similar one in Tennessee.

The Department of Mental Health has allocated extra resources to community health centers for mental health screenings, crisis stabilization units, mobile crisis response teams, and court liaisons; however, funding for transportation by law enforcement officers is not included.

According to Allen, it's more beneficial for sheriffs to focus on transportation instead of incarcerating individuals, as the expenses associated with transportation are minimal when compared to the potential liability risks of detaining someone who is going through a severe mental health crisis in a jail setting.

"That was basically the compromise," he explained. "They won't be incarcerated, but law enforcement will need to transport them."

Certain counties have investigated alternative solutions, such as setting up crisis stabilization units in closer proximity to residents.

Lee Caldwell, the County Supervisor, announced that DeSoto County is set to launch a 16-bed stabilization unit in Hernando this year. She noted that securing funding for the new facility promptly after the recent legislation posed challenges, but it was essential due to the considerable distance from the nearest crisis centers.

Certain proponents argue that the regulations outlined in the law require closer oversight by the government.

The legislation lacks any measures to guarantee that counties only detain individuals who fulfill the strict criteria set by the law—specifically, that there are no alternatives and the individual is “actively violent”—and it does not stipulate a maximum detention period of 48 hours.

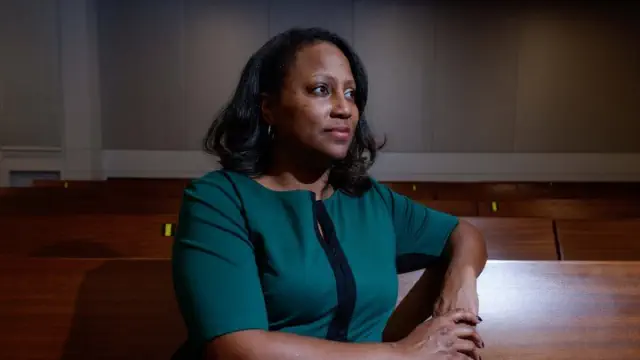

Greta Martin, who serves as the litigation director at Disability Rights Mississippi, expressed her concerns regarding the insufficient oversight present in the legislation.

"If you're passing a law that limits the time someone can be held in county jail to 48 hours, but you don't implement any measures to monitor whether county jails are following that rule, then what is the purpose of the law?" she remarked.

___

This story was originally published by Mississippi Today and distributed through a partnership with The Associated Press.